It starts with a hum—low, mechanical, and insistent. It might be the whine of a jet engine on the tarmac, the guttural thrum of a Harley-Davidson ready to launch, or the pulse of anticipation in your chest as the countdown hits one. At the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., the exhibit “America: Nation of Speed” is less a retrospective of machinery and more a meditation on velocity as a defining trait of American identity.

Opened in October 2022, the exhibition occupies Gallery 203 in the museum’s recently renovated west wing. Here, the notion of speed transcends horsepower and aerodynamics; it becomes a cultural artifact, a mirror held up to a nation forever in motion—relentless, bold, sometimes reckless. The layout is more than curatorial—it’s experiential, merging the tactile with the philosophical, the material with the mythic.

The first impression is not subtle. Near the entrance, Roscoe Turner’s RT-14 Meteor air racer stands frozen in mid-boast, its polished lines and flamboyant design recalling a moment in time when flight was both pageant and peril. Turner himself, a showman with a taste for theatrics, flew dressed in a quasi-military uniform, his mustache and medals part of the performance. His Meteor, a two-time winner of the Thompson Trophy, isn’t just a machine—it’s a vessel of American showmanship and the 1930s ethos of futurism.

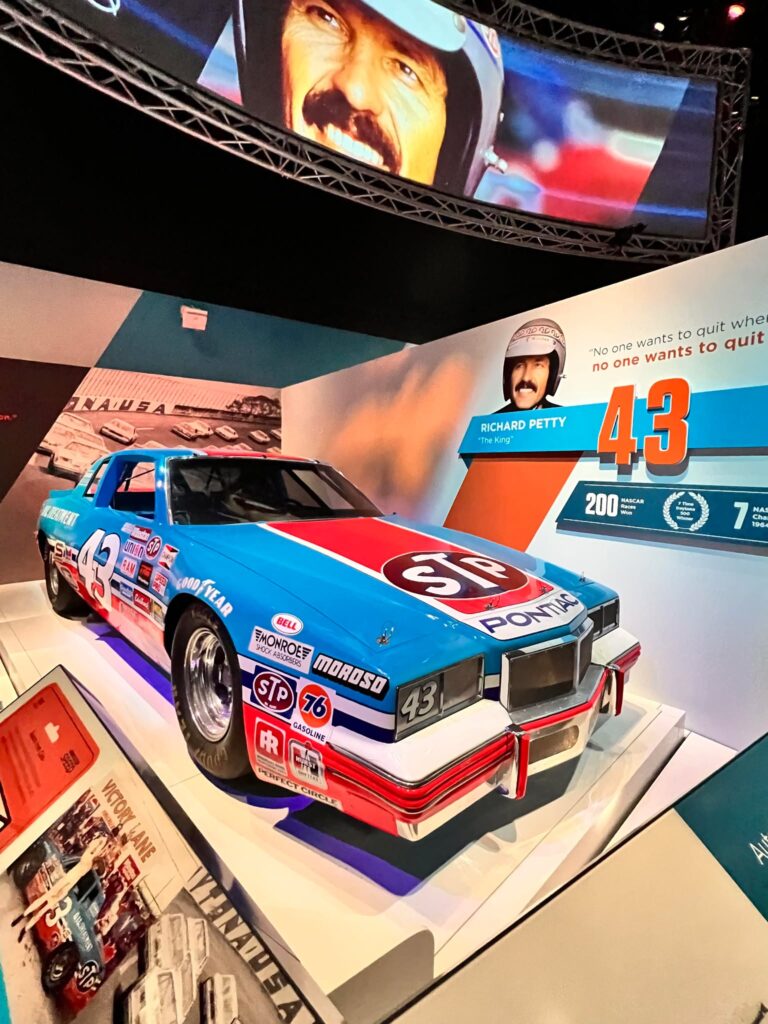

The exhibition deftly pivots between eras and disciplines. One moment you’re examining Mario Andretti’s 1969 Indianapolis 500-winning STP Hawk No. 2, the next, you’re staring down the launch rail of Sonic Wind No. 1, the rocket sled ridden by Col. John Stapp to test the thresholds of human endurance. These machines were born from different motives—some from the thrill of competition, others from the imperative of safety—but all share a common thread: the pursuit of limits.

More Than Aircraft in the Nation of Speed Exhibit

Andretti’s car is all muscle and precision; its aesthetic clean and unyielding, like the driver himself. Nearby, Evel Knievel’s battered Harley-Davidson XR-750 offers a counterpoint—less about winning, more about daring. Knievel didn’t just tempt fate; he commodified it. A nearby interactive pinball exhibit lets visitors tinker with the physics of his stunts, a nod to how spectacle and science often occupy the same stage.

If Knievel represents the populist edge of the Nation of Speed, Stapp’s Sonic Wind is its institutional face—government-funded, clinical, but no less audacious. In a series of tests during the 1950s, Stapp subjected himself to over 40 g’s of deceleration, essentially becoming a crash test dummy with a doctorate. His work informed everything from seatbelt standards to astronaut training. Here, speed was not about celebration, but survival.

That duality—between joyride and judgment—is present throughout the exhibit. A stark example: the Mark 4 Reentry Vehicle from a Titan I nuclear missile. Sleek and anonymous, it is a chilling reminder that speed, in the Cold War context, was about who could strike first. In a gallery filled with noise and motion, it is the silence of this artifact that lingers.

Elsewhere, speed reclaims its romanticism. The Sharp DR 90 Nemesis air racer, all sinew and sweep, appears ready to leap off its pedestal. It dominated races throughout the 1990s, its efficiency a marvel of design. And then there’s Erin Sills’ BMW S 1000 RR motorcycle, a machine so refined and relentless it shattered land-speed records in 2016, reaching 219.3 mph. Nearby, Glenn Curtiss’s 1907 V8 motorcycle—once the fastest thing on Earth—anchors the lineage. Hand-built, raw, almost archaic in appearance, it represents speed not as legacy, but as origin myth.

But the true impact of “Nation of Speed” lies not just in the artifacts, but in the connective tissue between them. A well-placed interactive called “Take the Controls” simulates the experience of piloting various vehicles at increasing speeds. It’s deceptively simple, and deeply revealing. The higher the speed, the narrower the margin for error. You come away understanding that speed isn’t just an engineering challenge—it’s a psychological one. Control is an illusion, tested at every turn.

There is something quintessentially American about this. Ours is a nation that equates movement with progress, velocity with virtue. From Manifest Destiny to the space race, the prevailing assumption has often been: faster is better. But as the exhibit quietly suggests, this belief is both the engine and the friction of the American experiment.

The deeper resonance of “Nation of Speed” is its ability to blur the lines between nostalgia and critique. Yes, there is admiration—earnest and unapologetic—for the ingenuity and courage that birthed these machines. But there’s also a subtle acknowledgment of the costs: environmental, psychological, existential. Every artifact is a triumph of its time, but also a question mark. What does it mean to always be chasing something faster?

In this way, the exhibit feels as relevant as it is retrospective. We live in a time where speed governs our digital lives, where the pace of innovation often outstrips our ability to adapt. In presenting speed as both aspiration and anxiety, the museum offers not just a showcase, but a reflection.

As you exit Gallery 203, you pass under an illuminated sign that reads simply: “EXIT.” But even that feels like part of the story. Outside, the world picks up its tempo. Traffic surges down Independence Avenue. Planes claw upward from nearby runways. The race, it seems, continues. But inside that gallery, for a moment, you are reminded that speed is more than a number on a dial. It is a language, a value system, a mirror.

And America? It speaks it fluently.

Going to DC next week, going to add this to my list.

We just went to see this history museum. In any case I did take pleasure in examining it.

Going to DC for a class trip and I am going to try to get over to see this

Merely a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw great style.